The Bare Minimum You Need to Know About LLMs

And what is a token? It is an arbitrary shard of text decided by a greedy compression algorithm that chops up language like a woodchipper with a hiccup.

Table of Contents

- It’s Just Autocomplete (But Really Good)

- Tokens: The Weird Unit That Will Haunt Your Dreams

- Input Tokens vs Output Tokens: The Billing Nightmare

- Context Window: The Model’s Goldfish Memory

- Parameters: The “Size” of the Model

- Proprietary vs Open Source (Open Weights)

- Cloud vs Local: The Ultimate Trade-off

- Model Sizes and Memory

- Quantization: Making Big Models Fit

- What You Actually Need to Remember

- Why This Matters for Your Actual Work

This is the boring technical shit you need to survive conversations about AI. We’re not doing the math. We’re not explaining transformers or attention mechanisms. We’re covering just enough so you don’t look like an idiot when someone mentions “tokens” or “context windows.”

Think of this as the Cliff Notes version that gets you through the interview without anyone realizing you learned all of this yesterday.

It’s Just Autocomplete (But Really Good)

Here’s the entire concept in one sentence:

LLMs predict the next word based on all the words that came before.

That’s it. That’s the whole thing.

You type “The capital of France is” and the model goes “I’ve seen this pattern ten thousand times in my training data, the next word is probably ‘Paris’.”

Everything else - the intelligence, the reasoning, the “emergent capabilities” people won’t shut up about - is just really impressive pattern matching at massive scale. The model doesn’t understand anything. It doesn’t think. It’s a very expensive parrot that’s read the entire internet and gotten really good at remixing it.

Does it sometimes seem intelligent? Sure. Is it? No. But neither is your coworker who copy-pastes from Stack Overflow, and they still have a job.

Tokens: The Weird Unit That Will Haunt Your Dreams

Here’s where it gets annoying: LLMs don’t actually work with words. They work with tokens. Words are shredded to chunks. Chunks become numbers. Math happens. Numbers become chunks again. Chunks reassemble into words. It’s like a document going through a blender and coming out the other side mostly intact. Mostly.

A token is roughly a word, but not exactly. And this matters because:

- You pay per token (there goes your coffee budget)

- Context limits are measured in tokens (hard limits you can’t negotiate with)

- The model sometimes acts weird because of how things get tokenized (and you’ll waste hours debugging it)

What is a token?

Think of tokens as “chunks” of text that some sadistic algorithm decided made sense. Usually:

- Common words are one token: “the”, “is”, “cat”

- Less common words get split: “tokenization” might be “token” + “ization”

- Numbers and special characters are a dice roll: “2024” might be one token or two, good luck

- Spaces and punctuation count: ” hello” (with space) is different from “hello” (without)

Here’s the fun part: a token is not always a word, and a word is not always one token.

The “egg” problem (or: why capitalization ruins everything)

Try this thought experiment:

- “egg” → 1 token

- “Egg” → 2 tokens (capital E gets split off like it committed a crime)

- “EGG” → 3 tokens (because why not make it worse)

The model “sees” these as completely different things. This is why it’s sometimes terrible at counting letters in words (it never saw the letters, just tokens) For the same reason it handles common words better than uncommon ones (common = one token, uncommon = TokenPurgatory), and it sometimes acts completely unhinged with capitalization or special characters.

Someone once spent three days debugging why their AI chatbot worked perfectly in English but broke on French names. Turns out “François” was being tokenized into four different pieces and the model was treating it like a corrupted file. The solution? They had to manually add the name to their preprocessing. This is your life now.

Why this is annoying

You don’t need to memorize tokenization rules (please don’t, you have better things to do). You just need to know:

- Tokens ≈ words, but not exactly

- You pay per token

- Token limits are real and will bite you at 3am

Rough math: 1 token ≈ 0.75 words, or about 4 characters. So 100 tokens ≈ 75 words. This is a lie, but it’s a useful lie for estimates.

Vocabulary Size: The Model’s Word List

Here’s something that makes the tokenization weirdness make slightly more sense: every model has a fixed vocabulary of tokens it knows.

Think of it like a dictionary. GPT-4 has roughly 100,000 tokens in its vocabulary. That’s 100,000 possible “chunks” it can work with. Common words and word pieces get their own tokens. Rare words get split into multiple pieces from the vocabulary.

Why this matters:

- The model literally cannot generate a token that’s not in its vocabulary

- This is why it’s bad at new slang, brand names, or technical jargon that didn’t exist during training

- This is why asking it to spell words can be weird (it’s thinking in tokens, not letters)

- Different models have different vocabularies, which is why the same text costs different amounts on different APIs

Ask GPT-3.5 to count the letters in “strawberry” and watch it fuck up. It sees “strawberry” as tokens, not as 10 individual letters. It’s like asking someone to count letters in a word they’ve only ever seen as a single hieroglyph.

The vocabulary is frozen at training time. The model learns patterns with those 100k tokens and that’s all it gets. Forever. Until someone trains a new model.

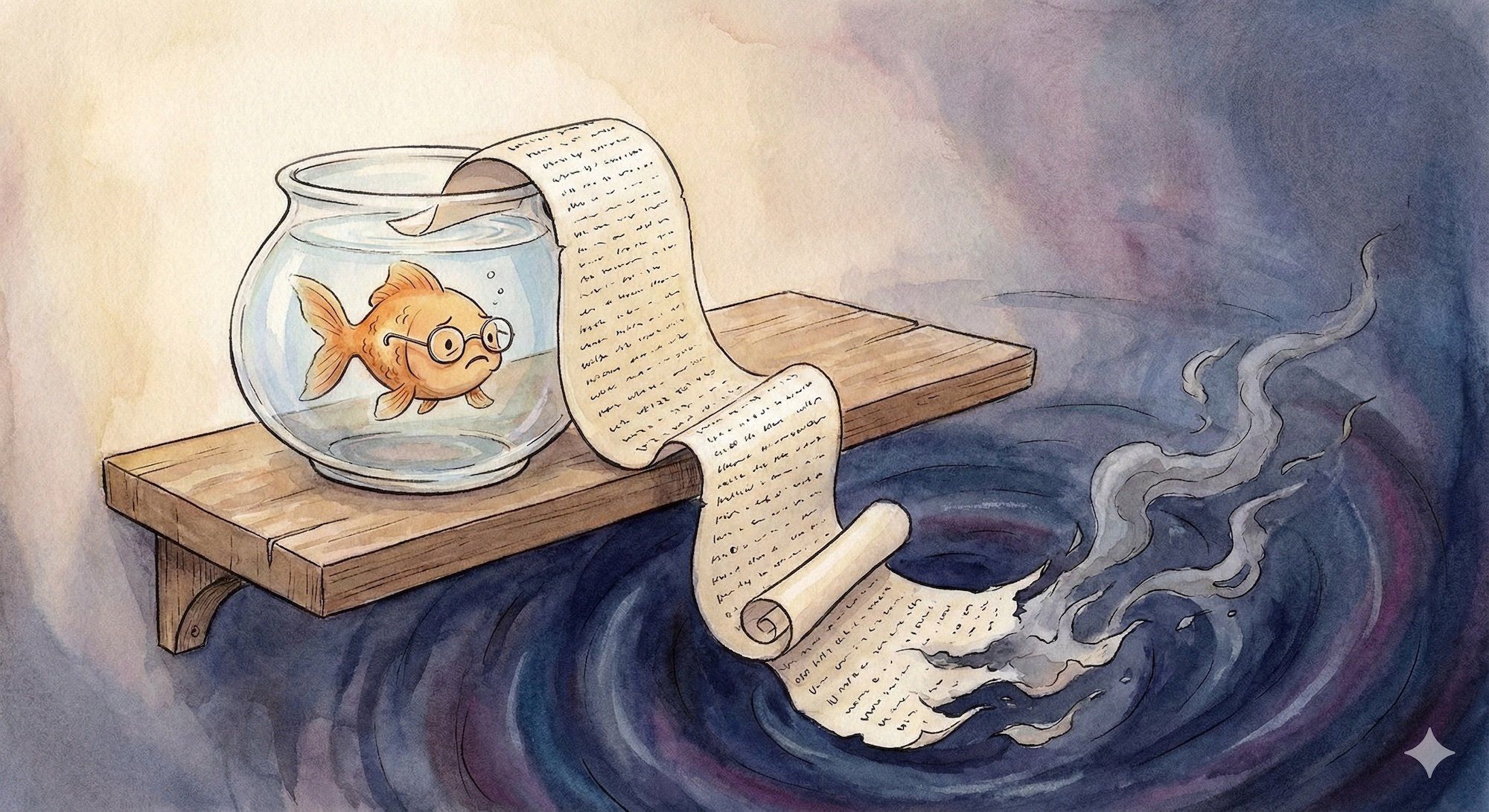

Context Window: The Model’s Goldfish Memory

LLMs have a context window - the maximum amount of text they can “see” at once. Think of it like RAM for the conversation, except when it runs out, things just vanish into the void instead of your computer crashing.

Older models context windows:

- GPT-4: 128k tokens (~96,000 words, or roughly the first three Harry Potter books)

- Sonnet-3.5: 200k tokens (~150,000 words, or the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy)

- Smaller models: 4k-32k tokens (a long email, maybe)

This sounds like a lot until you try to use it. Then you realize:

- Your entire conversation history counts against this limit

- Every message you send counts

- Every response the AI generates counts. Including thinking tokens.

- The system prompt (the hidden instructions)

- Any files or documents you include count too

- Once you hit the limit, the model starts “forgetting” the beginning of the conversation

- It doesn’t tell you it’s forgetting, it just starts making shit up based on vibes

This is why after a long conversation, the AI “forgets” what you talked about earlier. It’s not being dumb - it literally can’t see that part of the conversation anymore. The beginning just fell off the edge of its world. Flat earth, but make it silicon.

You’re debugging a complex issue with an AI.

You’ve been going back and forth for hours.

You’ve given it your entire codebase, your error logs, your database schema. It’s been helpful. Then suddenly it suggests something completely nonsensical that contradicts everything you told it 30 minutes ago.

You think: “Is the AI broken? Did I piss it off somehow?”

No. You just hit the context window limit.

Everything you said at the beginning? Gone. Vanished.

The AI is now working with half the information and doesn’t know it’s missing anything. It’s like trying to debug with someone who has amnesia but doesn’t realize it.

This will happen to you. You will waste time on it.

You’re welcome for the warning.

Why this matters for you

- Long conversations eventually break down (just start a new chat, it’s fine)

- Big codebases don’t fit in context (you have to be selective about what you show the AI)

- More context = more cost (you pay for every token in, every token out)

- The AI will not tell you when it forgets things (it just confidently makes stuff up with the remaining context)

The context window is why you’ll eventually need techniques like RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) to work with large amounts of data. But we’ll get to that torture later.

You would think models with bigger context windows are always better. Sadly, these models hallucinate too, but instead of forgetting the beginning of the conversation, they just forget the middle of it.

Input Tokens vs Output Tokens: The Billing Nightmare

When you use an LLM API, you pay for two things:

- Input tokens: Everything you send (your prompt, conversation history, any files)

- Output tokens: Everything the model generates (its response)

Usually output tokens cost more than input tokens (like 3-5x more), because generating is more expensive than reading. This creates some perverse incentives:

- Asking the AI to “explain in detail” costs way more than “be concise”

- Long conversations get expensive fast because the entire history is input tokens on every request

- That chatbot you built? Each message includes the entire conversation so far. Your AWS bill is going to be fun.

A startup built an AI customer service chatbot. Worked great in testing. They launched it. First week’s bill: $40,000. Why? Customers were having long conversations, and they were sending the entire conversation history on every single message. They were paying to send “Hello” + entire conversation + “How can I help?” hundreds of thousands of times.

They’re now very careful about conversation history management. You will be too, after your first bill.

Pro tip

If you’re using AI a lot, check the token counts. Most tools show you “X input tokens, Y output tokens” somewhere. Start noticing what costs money. That innocent “explain this in detail” request? That’s $0.50. Asked it 100 times today? That’s $50. Every day. Forever.

Since the advent of Thinking/Reasoning models, the number of output tokens are outragingly high compared to input tokens. This is because the model generates a lot of “thinking” tokens internally before giving you the final answer. And you pay for all of them.

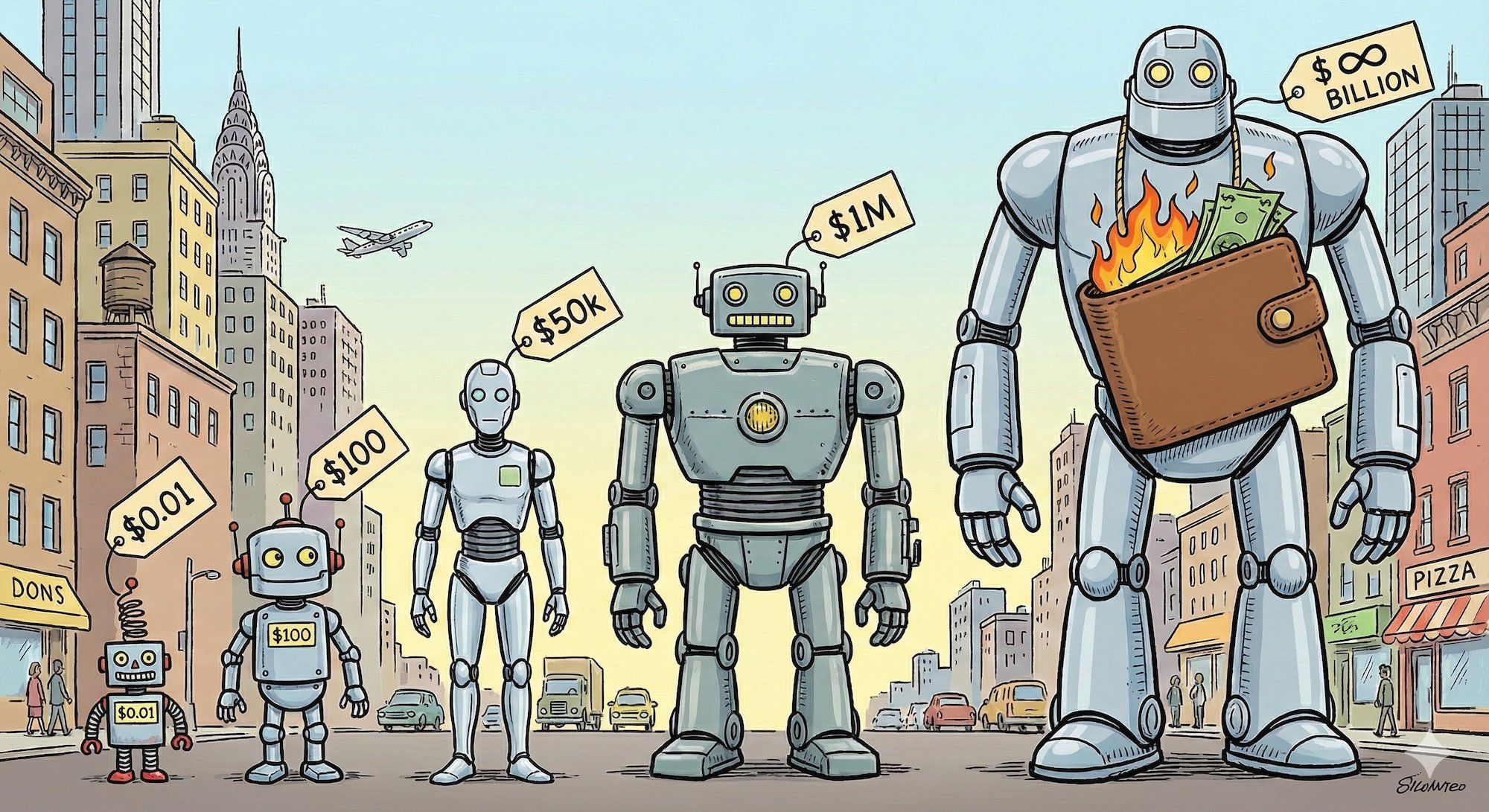

Parameters: The “Size” of the Model (And Your Ego)

You’ll hear people casually drop things like “GPT-4 has 1.7 trillion parameters” at parties (you go to terrible parties). What does that mean?

Parameters are the model’s learned patterns - the knobs that got tuned during training. Think of them as the model’s brain cells, except made of linear algebra instead of biology.

More parameters usually means:

- Smarter / more capable (can handle more complex patterns)

- More expensive to run (needs more GPU memory, more electricity, more money)

- Slower (more computation per token)

- More bragging rights in meetings

Model sizes you’ll see (at the start of 2026, because God knows what’s coming next):

- ~1B: Tiny models, mostly for experiments and edge deployments, very specialized

- 7B-13B: Small, fast, cheap, good for simple tasks, makes mistakes often

- 30B-70B: Medium, decent quality, reasonable cost, still makes mistakes

- 175B-1TB: Large (GPT-3.5, GPT-OSS, DeepSeek-V3.2), expensive, high quality, still makes mistakes but more eloquently

- 1T+: Cutting edge (GPT-5.2, Opus-4.5, Gemini 3), very expensive, SOTA, still makes mistakes but sounds super convincing

You don’t need to know the exact parameter counts. You just need to know: bigger = smarter but more expensive. It’s like buying a car. A Corolla gets you there. A Tesla gets you there faster, with more features, and a bigger monthly payment.

Here’s something nobody tells you: the parameter count doesn’t matter as much as everyone pretends it does. A well-trained 13B model can beat a poorly-trained 70B model. But everyone obsesses over the numbers because numbers are easy to compare and understanding actual quality is hard.

It’s like judging programmers by lines of code written. Everyone knows it’s stupid, everyone still does it.

Proprietary vs Open Source (Open Weights): The Eternal Debate

Proprietary models (GPT-4, Claude, Gemini):

- Accessed via API only (you get a REST endpoint and a prayer)

- Can’t see the model weights (it’s their secret sauce)

- Usually the most capable (they have the money to train big models)

- You pay per token (every request costs money)

- OpenAI/Anthropic/Google can change them anytime (one day your prompts work, next day they don’t)

- You’re completely at their mercy (rate limits, downtime, policy changes)

Open source models (Llama, Mistral, DeepSeek):

- Model weights are public (you can download all X gigabytes of them)

- You can download and run them yourself (if you have the hardware)

- Usually less capable (but catching up fast, which terrifies the proprietary vendors)

- Free to use (but you pay for compute if self-hosting, which isn’t actually free)

- More control, way more hassle

- You own your destiny (and your problems)

“Open source” in AI usually means “open weights” - you get the trained model, but not always the training code, the training data, or any clue how they actually built it. It’s like getting a compiled binary and calling it “open source.” But hey, it’s better than nothing.

The philosophical debate you’ll be forced into

Someone will eventually corner you at a meetup and passionately argue about open vs proprietary models. They will have Opinions™. Here’s what they won’t tell you:

- Proprietary models are easier but you’re locked in (the classic vendor lock-in, now with AI)

- Open models are “free” but running them costs money and time (someone’s gotta pay for those GPUs)

- By the time you set up local hosting for an open model, you could’ve spent $100 on API calls and shipped your feature

- But if you use APIs, you’re sending your data to someone else’s servers (goodbye, secrets)

There’s no right answer. Choose your poison based on your constraints, not your ideology. You should try local models at least for fun, it teaches you a lot about what is required to run these things.

Cloud vs Local: The Ultimate Trade-off

Cloud (API):

- Easy: just call an API (literally five lines of code)

- Pay per token (death by a thousand cuts)

- No GPU needed (your laptop from 2019 works fine)

- Fast (usually, until their servers are down)

- Zero control over the model (they can change it, rate limit you, or ban you tomorrow)

- Your data goes to their servers (hope you trust them)

Local (self-hosted):

- One-time cost (GPU hardware: $2,000-$50,000+)

- Free per request (but electricity isn’t free, and GPUs are space heaters)

- Full control and privacy (your data stays on your servers)

- Slower (unless you have a beast GPU that costs more than your car)

- Way more hassle (driver issues, CUDA errors, out of memory crashes, oh my)

- You’re now the sysadmin (congratulations, you played yourself)

For most developers: start with APIs. Only go local if you have a really good reason:

- You’re processing sensitive data that can’t leave your servers

- You’re doing this at massive scale and the math works out cheaper

- You have compliance requirements (HIPAA, GDPR, your lawyer is paranoid)

- You’re a masochist who enjoys CUDA driver debugging at 2am

Model Sizes and Memory: Why You Can’t Have Nice Things

If you decide to run a model locally (against all advice), here’s the brutal truth: the model needs to fit in your GPU’s memory (VRAM).

Not your RAM. Your GPU’s VRAM. That thing that’s measured in gigabytes, not terabytes.

Rough memory requirements:

- 7B model: ~14GB VRAM (barely fits on a consumer GPU, if you’re lucky)

- 13B model: ~26GB VRAM (needs a serious GPU, like $1,500+)

- 70B model: ~140GB VRAM (needs multiple GPUs, you’re looking at $10k+ easy)

This is why most people use APIs instead of running models locally - you’d need $5,000+ in GPUs just to run something decent. And that’s before you factor in:

- Electricity costs (GPUs are hungry)

- Cooling (your room is now a sauna)

- Your time (debugging CUDA is not fun)

- Upgrade cycles (GPU tech moves fast, your $5k investment is outdated in 18 months)

The local hosting fantasy: “I’ll just buy a GPU once and run models forever for free!”

The local hosting reality: You spend two weeks getting it working, run it for a month, realize the electricity cost + your time makes it more expensive than APIs, then quietly switch to Claude and never speak of it again.

Dense vs Mixture-of-Experts (MoE): The Memory Trick

This is getting into the weeds, but you’ll hear these terms in blog posts written by people trying to sound smart:

Dense models: Load all parameters into VRAM. Simple. Everything’s in GPU memory all the time. Memory-hungry as hell.

Mixture-of-Experts (MoE): Only load the “expert” layers you need for each request. The rest stays in regular RAM. More memory-efficient, but architecturally more complex. Think of it like lazy loading for neural networks.

You don’t need to understand MoE deeply. Just know: it’s a trick to run bigger models on less powerful hardware. It works sometimes. It’s finicky other times. You’ll read papers about it and feel smart.

Reality check: Unless you’re working at a company building LLMs, you’ll probably never need to care about dense vs MoE. But knowing the terms makes you sound informed in meetings.

Macs with M1 or later chips use unified memory architecture, which means the GPU and CPU share the same memory pool. This can help with smaller models (7B-13B) since you don’t have to worry about separate VRAM, but performance may not match dedicated GPUs for larger models.

Up to 75% of the memory can be used for GPU tasks = AI tasks, but this varies based on workload and system configuration.

Just something to keep in mind if you’re on a Mac.

Quantization: Making Big Models Fit

Here’s a technique that sounds like yet another voodoo incantation but is actually simple: quantization is making numbers smaller so the model takes up less space.

When a model is trained, all those billions of parameters are stored as high-precision numbers (usually 16-bit or 32-bit floats). Quantization says “what if we stored them as smaller numbers instead?” Like 8-bit, 4-bit, or even 2-bit integers.

The trade-off: Lower precision but fits in less VRAM / slightly worse quality but faster inference (smaller numbers = faster math)

Common quantization levels:

- 16-bit (FP16): Basically full quality, half the size of 32-bit

- 8-bit (INT8): Minimal quality loss, half the size of FP16

- 4-bit (INT4): Noticeable but acceptable quality loss, very small

- 2-bit: Exists, but quality gets rough

Why this matters: If you’re running models locally, quantization is how you fit a 70B model on a consumer GPU. A 70B model at full precision needs ~140GB of VRAM (lol, good luck). The same model quantized to 4-bit needs ~35GB (still a lot, but achievable with a good GPU).

The reality:

- For APIs: You don’t care, they handle this

- For local hosting: You’ll use quantized models because you have to

- For interviews: Knowing what quantization is makes you sound smart

Most local model tools (like Ollama, LM Studio, llama.cpp) automatically use quantized versions. You’ll see model names like “llama-70b-q4” where “q4” means “4-bit quantization.”

Speaking of inference: inference just means “using the model.” When you send a prompt and get a response, that’s inference. It’s the opposite of training. Training = teaching the model. Inference = using what it learned. That’s it.

Quantization is for inference. You can’t really train a model effectively with 4-bit quantization because the precision loss breaks the learning process. But for just using a trained model? Works great.

What You Actually Need to Remember

Here’s the cheat sheet for when someone (like us) inevitably quizzes you on this stuff:

Tokens:

- Not exactly words, roughly 0.75 words per token (close enough for estimation)

- You pay per token (input + output, output costs more)

- Token limits are real (and will ruin your day when you hit them)

- Tokenization is weird (capitalization matters, special characters are chaos)

- Models have a fixed vocabulary of tokens

Input vs Output Tokens:

- Input = what you send (prompt, history, files)

- Output = what the model generates (its response)

- Output tokens cost 3-5x more than input

- Conversation history accumulates fast

Context Window:

- How much text the model can “see” at once

- Currently 200k-1M tokens for good models (sounds like a lot, isn’t)

- Everything counts: your messages, AI responses, all history

- When you hit the limit, the model forgets without telling you

Parameters:

- The “size” of the model (bigger number = bigger model)

- More = smarter but more expensive and slower

- 7B = small, 70B = medium, 175B+ = large, 1T+ = cutting edge

- People obsess over this number more than they should

Proprietary vs Open:

- Proprietary = API only, usually best, vendor lock-in (GPT-5, Claude)

- Open = you can download it, more control, more hassle (Llama, Mistral)

- Most people should use APIs (at least to start)

Cloud vs Local:

- Cloud = API, easy, pay per use, send data to someone else

- Local = self-host, one-time cost (lol), total control, total responsibility

- Start with cloud (seriously, just do it)

Quantization:

- Makes models smaller by using lower-precision numbers

- 16-bit = full quality, 8-bit = minimal loss, 4-bit = noticeable but usable

- Essential for running big models locally

- APIs handle this for you

Inference:

- Just means “using the model” (as opposed to training it)

- When you send a prompt and get a response, that’s inference

That’s it. That’s the bare minimum. You can now survive a conversation about LLMs without sounding clueless. You might even sound knowledgeable if the other person knows less than you.

Why This Matters for Your Actual Work

Understanding tokens and context windows helps you:

- Debug prompts: “Why did it forget my instructions?” → You hit the context limit

- Manage costs: “Why is my bill so high?” → Check your token usage, probably that chatbot

- Choose models: “Should I use GPT-4 or a smaller model?” → Depends on task complexity, budget, and how much you like money

- Build better features: “Why does my AI feature break on long conversations?” → Context window management, welcome to the pain

You don’t need to be an expert. You just need to know enough to not be surprised when things break (they will break, they always break).

The Part Where It Gets Real

Here’s what nobody tells you in the Medium articles and conference talks:

-

Working with LLMs means working with something non-deterministic (gives different answers), probabilistic (maybe correct, maybe not), and with hard limits (tokens, context windows) that you can’t negotiate with. It’s like programming drunk - things sort of work, but you’re never quite sure why, and sometimes it all falls apart for reasons you can’t explain.

-

You’ll spend hours debugging why a prompt worked yesterday but doesn’t today (they updated the model). You’ll watch your token costs spiral because you forgot conversation history accumulates (rookie mistake). You’ll hit context limits at the worst possible time (during a demo, obviously).

This is normal. This is everyone’s experience. Anyone who tells you otherwise is lying or selling something.

The good news? Once you understand these basics - tokens, context windows, the fact that it’s all just autocomplete - you can work around the limitations. You’ll build things that work. Maybe not elegantly. Maybe not the way you’d prefer. But they’ll ship. Sometimes.

And that’s all you need.